What I Wish I Knew Before Quitting My Job to Start a Business

Leaving a stable career to start a business is exciting—but risky. I learned this the hard way. What looked like freedom turned into financial stress, sleepless nights, and near burnout. I underestimated costs, overestimated income, and ignored red flags. This isn’t a success story. It’s a real talk about the hidden traps in career transitions. If you’re thinking about jumping ship, here’s what you *really* need to know about managing risk—and staying sane.

The Leap That Almost Broke Me

The day I handed in my resignation, I felt like I was stepping into a new life. No more early commutes, no more office politics, no more answering to a manager. I had saved some money, drafted a business plan, and believed I was ready. I was launching a small consulting firm based on skills I’d built over ten years in corporate marketing. How hard could it be? Within three months, I realized I had traded one set of problems for a whole new category of stress.

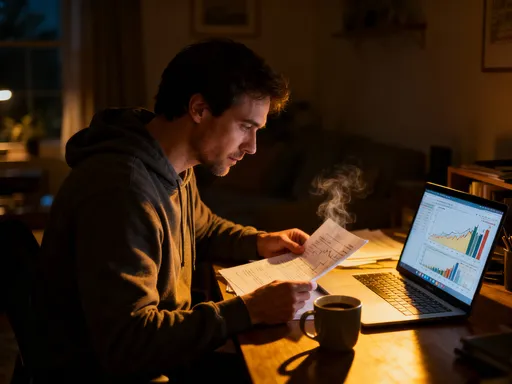

At first, the freedom was intoxicating. I set my own hours, worked from home, and wore sweatpants all day. But that freedom quickly revealed its cost. Without the structure of a job, my days blurred together. Some days I was hyper-focused. Others, I struggled to start anything. The biggest shock was the income—or lack of it. My first month brought in $1,200. The next, only $400. I had assumed clients would come steadily, but instead, I was chasing leads, sending proposals, and waiting—often in silence. Meanwhile, bills didn’t stop coming.

What I didn’t anticipate was the psychological toll. In a job, even a stressful one, there’s predictability. Payday comes every two weeks. Benefits are automatic. Performance reviews, while nerve-wracking, provide feedback. As a business owner, I had none of that. I was alone with my decisions, my doubts, and my mounting anxiety. The financial uncertainty began to affect my sleep, my relationships, and even my confidence. I started questioning whether I had made a huge mistake. The dream of independence was real, but so was the risk—and I had walked into it unprepared.

Underestimating the True Cost of Going Solo

One of the most common mistakes aspiring entrepreneurs make is focusing only on startup costs while ignoring the ongoing expenses of running a business—and supporting oneself. When I planned my exit, I calculated the cost of a laptop, a website, and some software subscriptions. I thought I could live off $3,000 a month, so I told myself I’d be fine if I made $4,000. What I failed to account for was everything that wasn’t in my old paycheck.

At my previous job, health insurance was covered. Now, I had to pay $450 a month for a basic plan. Retirement contributions? Gone. Paid time off? A distant memory. Taxes became my new enemy. As a self-employed person, I was responsible for both the employer and employee portions of Social Security and Medicare—adding nearly 15.3% to my tax burden. Then there were business expenses: accounting software, liability insurance, co-working space when I needed a change of scenery, and professional development courses to stay competitive.

When I added it all up, my monthly burn rate—the amount I needed just to survive and keep the business running—was closer to $5,200. That meant I needed to earn nearly $7,000 a month just to break even after taxes. My initial revenue projections, which assumed $5,000 a month by month six, suddenly looked dangerously optimistic. The gap between income and expenses became a chasm. I dipped into savings faster than I expected, and within eight months, I had burned through nearly half of my emergency fund. The lesson was clear: financial runway isn’t just about how long you can survive without income. It’s about understanding every dollar that leaves your account—and planning for the ones that won’t come in.

The Income Illusion: When Projections Lie

Every business plan includes revenue projections. Most of them are wrong—especially in the first year. Mine was no exception. I based my income forecast on the average fees I charged as a contractor while still employed. I assumed that if I could land two clients a month, I’d be stable. What I didn’t factor in was the sales cycle, client churn, and the reality that not every lead turns into a paying customer.

In my first year, I landed seven clients. That sounds decent—until you realize three of them paid only once and never returned. One client delayed payment for 90 days, creating a cash crunch that forced me to delay my own expenses. Another asked for a steep discount, cutting my margins in half. My actual average monthly income? Just under $3,800—nearly 30% below my conservative estimate. And that number doesn’t include the months when I earned nothing at all.

The danger of over-optimistic projections isn’t just financial. It’s behavioral. Because I believed I would earn $5,000 a month, I adjusted my lifestyle. I upgraded my internet plan, bought new business cards, and even took a short trip, telling myself I’d earned it. When the income didn’t materialize, I had to reverse those decisions, often at a loss. The bigger cost was credibility. I couldn’t invest in marketing or professional development because I was covering basic expenses. I was stuck in a cycle of survival, not growth. The truth is, early revenue is rarely steady, and assuming it will be can lead to poor financial decisions. A better approach is to build your budget on worst-case scenarios, not best guesses.

Risk #1: No Safety Net, No Backup Plan

The most dangerous moment in any career transition is the point of no return—the day you walk away from your job with no way back. I reached that point too soon. I had savings, but not enough to cover more than a year of expenses. I didn’t have a side hustle generating income. I wasn’t doing freelance work on the side. I had bet everything on my new business succeeding quickly. When it didn’t, I had no fallback.

Having no safety net doesn’t just hurt your finances. It distorts your judgment. When you’re desperate for money, you accept bad clients, undercharge for your work, and take on projects that drain your energy. I found myself saying yes to every opportunity, even if it wasn’t a good fit, because I couldn’t afford to say no. That led to burnout and resentment—toward my clients, my business, and myself. I wasn’t building a sustainable venture. I was trying to survive.

A financial buffer changes everything. It gives you the breathing room to make strategic decisions, not just reactive ones. Experts often recommend having 6 to 12 months of living expenses saved before leaving a job. In my case, I had eight months—but that was based on my old, lower cost of living. Once I accounted for insurance, taxes, and business costs, my real runway was closer to five months. That made all the difference. A true safety net isn’t just about savings. It’s about redundancy. It means keeping a part-time job, maintaining freelance clients, or having a spouse or partner with stable income. It means being willing to slow down the transition to reduce risk. The goal isn’t to avoid risk altogether—that’s impossible in entrepreneurship. It’s to ensure that if things go wrong, you don’t lose everything.

Risk #2: Ignoring Market Realities

Passion is a powerful motivator, but it’s a poor business model. I learned this when I launched a side product based on an idea I loved: a curated newsletter for busy professionals who wanted to stay informed without spending hours online. I believed in it deeply. I spent weeks designing it, writing sample content, and building an email list. I even pre-sold subscriptions. But within three months, cancellations outweighed new sign-ups. By month six, I shut it down.

The problem wasn’t the quality of the product. It was the market. I had assumed that because I wanted this service, others would too. I didn’t test the idea with real users before investing time and money. I didn’t ask potential customers what they were already using or what they were willing to pay. I didn’t analyze competitors or pricing models. I built something in a vacuum—and it showed.

This failure cost me more than just time. It cost me confidence and resources I couldn’t afford to lose. But it also taught me one of the most valuable lessons in business: validate before you build. Market research doesn’t have to be complex. It can be as simple as talking to ten potential customers, running a low-cost ad to test interest, or offering a pilot version to a small group. The goal is to gather real data, not rely on assumptions. Many entrepreneurs fall into the trap of confirmation bias—seeking evidence that supports their idea while ignoring red flags. A smarter approach is to assume your idea might fail and design small, low-cost experiments to prove it right. That way, you invest money only when you have evidence of demand.

Risk #3: Wearing Too Many Hats (and Doing Them Poorly)

One of the myths of entrepreneurship is that you have to do everything yourself. In the early days, I believed that too. I was the CEO, marketer, accountant, customer service rep, and web designer. I thought saving money by handling tasks myself was smart. What I didn’t realize was the hidden cost: my time.

Time is a finite resource, and how you spend it determines your business’s growth. I spent hours learning how to use accounting software, only to make mistakes that cost me in taxes. I designed my own website using a template, but it didn’t convert visitors into leads. I wrote my own ads, but they didn’t speak to my audience. These tasks were outside my expertise, and the results showed. I wasn’t saving money—I was losing opportunities.

The turning point came when I hired a freelance bookkeeper for $200 a month. In two hours, she caught errors that could have cost me hundreds in penalties. She set up a system that saved me ten hours a month. That was the moment I realized: outsourcing isn’t a luxury. It’s a strategic move. The same went for marketing and design. When I invested in professional help, my conversion rates improved, my brand looked more credible, and I had more time to focus on client work—the highest-value activity I could do.

The lesson isn’t that you should outsource everything. It’s that you should focus on what only you can do. For most entrepreneurs, that’s delivering the core service or product. Everything else—administration, marketing, tech support—can often be delegated, automated, or eliminated. Tools like scheduling software, email templates, and cloud accounting platforms can reduce the burden. The goal is to work *on* your business, not just *in* it. When you stop trying to do it all, you create space for growth.

Smart Risk Management: Protecting Yourself While Moving Forward

Entrepreneurship doesn’t have to be a leap into the unknown. It can be a series of small, deliberate steps that reduce risk while building momentum. Looking back, I wish I had taken a phased approach. Instead of quitting my job cold turkey, I could have started my business on the side, tested my services with real clients, and built a pipeline before making the full transition. That’s what many successful entrepreneurs do—and it’s one of the smartest strategies for long-term sustainability.

A side-hustle model allows you to validate your idea without financial pressure. You can refine your offering, build a client base, and generate early revenue while keeping your safety net intact. Once you reach a point where your side income consistently covers a portion of your living expenses, the risk of going full-time drops significantly. Contract work is another low-risk path. Many former employees transition by offering their skills as independent consultants to their former employers or industry contacts. This provides immediate income and credibility while building a portfolio.

Diversifying income streams is another key strategy. Relying on one client or one service is risky. Adding multiple offerings—such as digital products, group coaching, or affiliate partnerships—can create stability. Equally important is the non-financial side of risk management: mentorship, accountability, and mental resilience. Talking to someone who’s been through the journey can help you avoid common pitfalls. Regular financial check-ins—monthly reviews of income, expenses, and goals—keep you grounded in reality. And prioritizing mental health—through exercise, sleep, and boundaries—ensures you don’t burn out.

Starting a business is never risk-free. But risk doesn’t have to mean recklessness. With careful planning, realistic expectations, and disciplined execution, you can move forward with confidence. The goal isn’t to eliminate fear. It’s to respect it, prepare for it, and manage it wisely. That’s how you build not just a business, but a sustainable, fulfilling future.